"I walk on untrodden ground. There is scarcely any part of my conduct which may not hereafter be drawn into precedent."

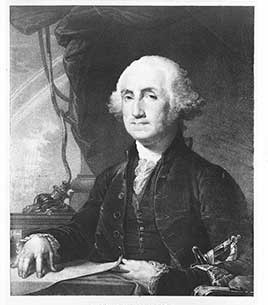

— George Washington, 1789George Washington understood better than anyone that his presidency would define the office for all time. When he took the oath of office on April 30, 1789, at Federal Hall in New York City, he was not simply becoming the first president—he was creating the presidency itself. Every decision, from the title by which he should be addressed to the proper relationship with Congress, would establish precedents that would guide the republic for generations.

This extraordinary man—farmer, surveyor, soldier, revolutionary, and statesman—possessed the unique combination of qualities necessary to launch the American experiment. His unimpeachable character provided the moral authority essential for democratic governance, while his practical experience managing Mount Vernon's 8,000 acres and commanding the Continental Army through eight years of revolution gave him the administrative and leadership skills to build effective institutions from nothing.

Early Life: Forging Character in Colonial Virginia

Born into Virginia's planter aristocracy, George Washington lacked the formal education of contemporaries like Jefferson or Adams. His father Augustine died when George was only eleven, ending hopes for schooling in England. Instead, Washington received a practical education that would prove exceptionally valuable: surveying taught him strategic thinking and frontier knowledge, while his transcription of "Rules of Civility and Decent Behaviour" at age fourteen instilled the self-discipline and dignity that would define his leadership style.

This early emphasis on character development shaped Washington's entire approach to life and leadership. The 110 rules he copied emphasized personal conduct, respect for others, and social responsibility—values that would guide him through the moral complexities of revolution, slavery, and democratic governance. As historian Ron Chernow observed, these rules "taught him to discipline his emotions and present a composed face to the world."

His marriage to Martha Dandridge Custis in 1759 brought both financial security and deep personal partnership. Martha's wealth, including 84 enslaved people, enabled Washington to focus on public service while developing the administrative skills managing Mount Vernon that would prove essential during his presidency. More importantly, their relationship demonstrated the mutual respect and support that would sustain him through decades of public service.

Fascinating Facts About Washington

- Only president elected unanimously by the Electoral College (twice)

- Never lived in the White House (completed after he left office)

- Owned more than 50,000 acres of land across five states

- Started the tradition of the inaugural address

- Created the first presidential cabinet

- Established the two-term precedent that lasted until FDR

- One of only three presidents who owned a distillery

- Lost more battles than he won, but won the war

- In his will, freed all of his enslaved people upon Martha's death

- His dentures were not wooden but made from ivory and human teeth

Military Leadership: The Making of a Revolutionary

Washington's military experience during the French and Indian War (1754-1758) provided crucial lessons in crisis management and strategic patience. Despite early defeats, including the surrender at Fort Necessity, he demonstrated remarkable courage during General Braddock's catastrophic defeat at Monongahela, where he had two horses shot from under him yet continued fighting. These formative experiences taught him that leadership required not just bravery, but the ability to maintain composure and inspire confidence during desperate circumstances.

His selection as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army in 1775 reflected his unique qualifications: military experience, Virginia origins (crucial for uniting the colonies), and proven commitment to the American cause. His leadership during eight years of revolutionary warfare demonstrated the strategic patience and moral authority that would characterize his presidency.

Revolutionary War Leadership

- Strategic Vision: Understood the war was about survival, not quick victory

- Character under Fire: Maintained army morale through darkest periods

- Political Astuteness: Worked effectively with Continental Congress

- International Diplomacy: Supported alliance-building with France

- Military Innovation: Adapted European tactics to American conditions

- Civilian Authority: Never challenged congressional supremacy

The Constitutional Convention: Creating a Framework

The period between war's end and constitutional ratification revealed Washington's evolving vision of American governance. His experience under the Articles of Confederation convinced him that stronger federal authority was essential. As he wrote in 1786, the national government appeared "always moving upon crutches, & tottering at every step."

His presiding role at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 lent crucial legitimacy to the new framework. While he spoke little during debates, his presence assured delegates and the public that the new government would be led by men of character. His unanimous election as president reflected not just personal popularity, but the nation's trust that he would implement the Constitution fairly and effectively.

The Presidential Challenge: Building from Nothing

When Washington assumed office, the United States faced existential challenges that threatened its survival. The nation consisted of only eleven states (North Carolina and Rhode Island had not yet ratified the Constitution) with approximately 4 million people. The federal government inherited an $80 million debt with only $4.4 million in annual revenue, no executive departments, no federal courts, and no established precedents for governance.

Internationally, the United States commanded little respect. Britain retained possession of western forts, Spain controlled the Mississippi River's mouth, and Barbary pirates attacked American shipping with impunity. The challenge was not merely governing effectively, but proving that republican government could work in practice—that a large nation could be governed by popular consent rather than monarchical authority.

Path to the Presidency

Creating the Presidency: Innovation and Precedent

Washington's greatest achievement was not merely serving as president, but creating the presidency itself. The Constitution provided only a skeletal outline of presidential powers; Washington's presidency gave these powers substance and form through carefully considered precedents that continue to guide executive behavior today.

His creation of the cabinet system, despite no constitutional provision for such an institution, demonstrated his practical approach to governance. His original four-member cabinet—Thomas Jefferson (State), Alexander Hamilton (Treasury), Henry Knox (War), and Edmund Randolph (Attorney General)—established the collaborative yet hierarchical decision-making process that remains central to presidential governance.

Equally important was his approach to presidential dignity and democratic accessibility. He rejected monarchical titles like "His Majesty" proposed by the Senate, insisting on the simple "Mr. President." His careful balance of republican simplicity with executive authority established standards for presidential conduct that enhanced respect for democratic institutions without creating an imperial presidency.

Character and Leadership Style

Washington's leadership style combined decisive authority with careful consultation, strategic vision with tactical flexibility, and personal humility with institutional dignity. Contemporary accounts consistently emphasize his exceptional self-control and commanding presence. Thomas Jefferson, despite later political differences, wrote that Washington's "integrity was most pure...his justice the most inflexible I have ever known."

This moral authority proved essential during partisan crises that threatened national unity. When newspapers attacked his administration and personal character, Washington's consistent ethical behavior and dignified responses maintained public confidence in democratic institutions. His refusal to respond to personal attacks established the precedent that presidents should remain above partisan warfare while defending legitimate policy differences.

Perhaps most remarkably, Washington understood that his greatest service to democracy would be knowing when to leave. His voluntary retirement after two terms, despite no constitutional limitation and calls for him to continue, demonstrated that American democracy could transcend individual leadership. King George III reportedly said that if Washington voluntarily relinquished power, "he will be the greatest man in the world."

The Complex Legacy of Slavery

Washington's relationship with slavery represents the most troubling aspect of his legacy. Despite owning over 300 enslaved people at Mount Vernon, Washington gradually developed private opposition to slavery that culminated in his will's provision to free his slaves after Martha's death—an unprecedented action among Virginia planters of his era.

His evolution on slavery showed moral growth that distinguished him from many contemporaries, though political calculations prevented public anti-slavery positions during his presidency. His private correspondence reveals increasing discomfort with slavery's contradiction of American liberty, representing the moral complexity that defined the founding generation's relationship with this institution.

Historical Standing and Continuing Relevance

Modern scholarship consistently ranks Washington among America's greatest presidents, typically in the top three with Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt. His precedents continue to guide presidential behavior and constitutional interpretation. The Twenty-Second Amendment's formalization of the two-term limit, the continuing operation of the cabinet system, and the ongoing relevance of executive privilege demonstrate that Washington's institutional innovations remain central to American governance.

Washington's example of nonpartisan leadership, ethical conduct, and institutional building provides continuing guidance for democratic leadership. His understanding that democracy requires leaders willing to transcend personal and partisan interests remains relevant for contemporary challenges to democratic governance. As historian Joseph Ellis observed, "Washington's genius was his understanding that power in a republic comes from giving it up."